Every decision a person makes stems from the person's values and goals. People can have many different goals and values; fame, profit, love, survival, fun, and freedom, are just some of the goals that a good person might have. When the goal is a matter of principle, we call that idealism.

My work on free software is motivated by an idealistic goal: spreading freedom and cooperation. I want to encourage free software to spread, replacing proprietary software that forbids cooperation, and thus make our society better.

That's the basic reason why the GNU General Public License is written the way it is—as a copyleft. All code added to a GPL-covered program must be free software, even if it is put in a separate file. I make my code available for use in free software, and not for use in proprietary software, in order to encourage other people who write software to make it free as well. I figure that since proprietary software developers use copyright to stop us from sharing, we cooperators can use copyright to give other cooperators an advantage of their own: they can use our code.

Not everyone who uses the GNU GPL has this goal. Many years ago, a friend of mine was asked to rerelease a copylefted program under noncopyleft terms, and he responded more or less like this:

“Sometimes I work on free software, and sometimes I work on proprietary software—but when I work on proprietary software, I expect to get paid.”

He was willing to share his work with a community that shares software, but saw no reason to give a handout to a business making products that would be off-limits to our community. His goal was different from mine, but he decided that the GNU GPL was useful for his goal too.

If you want to accomplish something in the world, idealism is not enough—you need to choose a method that works to achieve the goal. In other words, you need to be “pragmatic.” Is the GPL pragmatic? Let's look at its results.

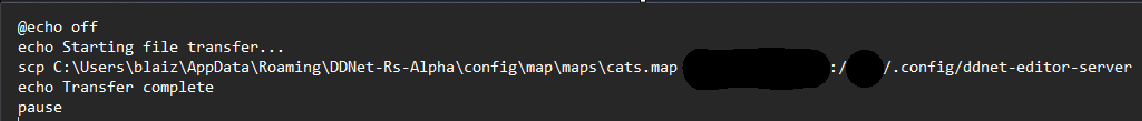

?

?